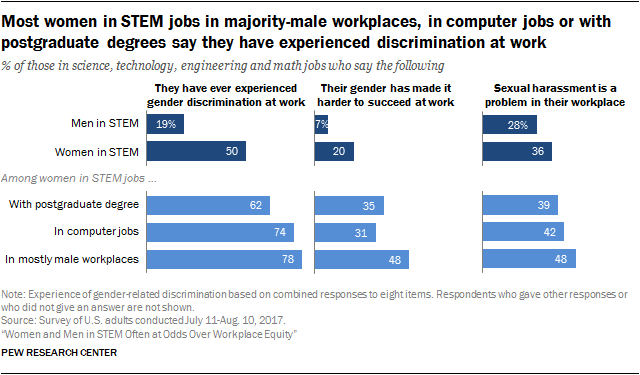

For women working in science, technology, engineering or math (STEM) jobs, the workplace is a different, sometimes more hostile environment than the one their male coworkers experience. Discrimination and sexual harassment are seen as more frequent, and gender is perceived as more of an impediment than an advantage to career success. Three groups of women in STEM jobs stand out as more likely to see workplace inequities: women employed in STEM settings where men outnumber women, women working in computer jobs (only some of whom work in the technology industry), and women in STEM who hold postgraduate degrees. Indeed, a majority of each of these groups of STEM women have experienced gender discrimination at work, according to a nationally representative Pew Research Center survey with an oversample of people working in STEM jobs.

These findings come amid heightened public debate about underrepresentation and treatment of women – as well as racial and ethnic minorities – in the fast-growing technology industry and decades of concern about how best to promote diversity and inclusion in the STEM workforce. Conducted in the summer of 2017, prior to the recent outcry about sexual harassment by men in positions of public prominence, the Center’s new survey findings also speak to the broader issues facing women in the workplace across occupations and industries.1

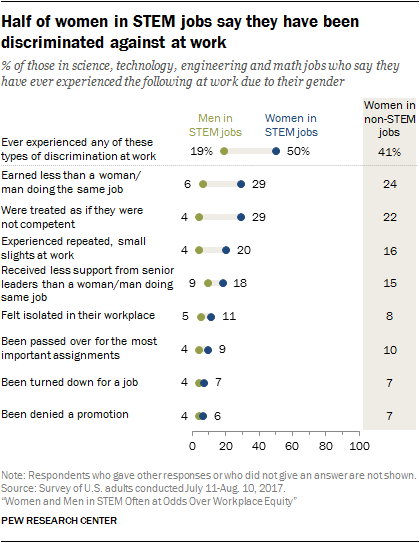

Compared with those in non-STEM jobs, women in STEM are more likely to say they have experienced discrimination in the workplace (50% vs. 41%). But in other respects, the challenges women in STEM face in the workplace echo those of all working women. Women in STEM and non-STEM jobs are equally likely to say they have experienced sexual harassment at work, and both groups of women are less inclined than men to think that women are “usually treated fairly” when it comes to promotions where they work.

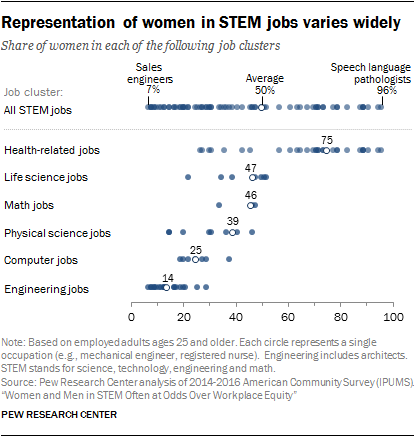

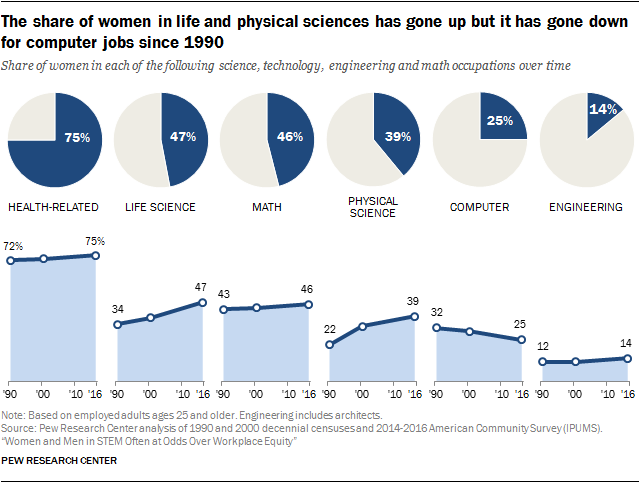

Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data since 1990 shows that while jobs in STEM have grown substantially, particularly in computer occupations, the share of women working in STEM jobs has remained at about half over time. But the share of women varies widely across the 74 standard occupations classified as STEM in this study – from under one-in-ten for sales engineers (7%) and mechanical engineers (8%) to 96% of speech language pathologists and 95% of dental hygienists. Women are a majority of those working in health-related occupations but just 14%, on average, of those in engineering jobs. In computer occupations, a job cluster which includes computer scientists, systems analysts, software developers, information systems managers and programmers – the STEM job cluster that has seen the most growth in recent decades – women’s representation has actually decreased from 32% in 1990 to 25% today.

Blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented in STEM occupations relative to their share in the U.S. workforce. The share of blacks working in STEM jobs has gone from 7% in 1990 to 9% today (blacks make up 11% of the total U.S. workforce today). And that for Hispanics has gone up from 4% to 7%, while their share of the U.S. workforce has grown from 7% in 1990 to 16% today.

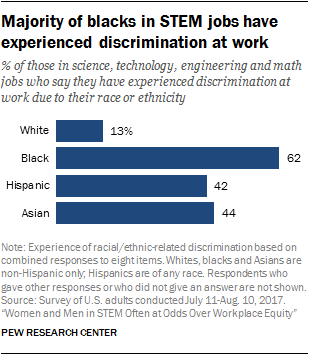

The survey finds a higher share of blacks in STEM jobs report experiencing any of eight types of racial/ethnic discrimination (62%) than do others in STEM positions (44% of Asians, 42% of Hispanics and just 13% of whites in STEM jobs say this). They also tend to do so more than blacks in non-STEM jobs (50%), with many saying they have been treated as if they were not competent because of their race or ethnicity.2 Blacks in STEM jobs are particularly likely to say there is too little attention to racial and ethnic diversity where they work (57%). And, when it comes to the way opportunities for advancement and promotion are handled in their own workplace, 37% of blacks in STEM jobs believe that blacks are usually treated fairly, while a similar share (36%) says this sometimes occurs and 24% believe that blacks are usually treated unfairly where they work. Among Hispanics, those in STEM and non-STEM jobs are equally likely to say they have experienced racial/ethnic workplace discrimination.

These are some of the findings from a Pew Research Center survey with a nationally representative sample of 4,914 adults (including 2,344 STEM workers), ages 18 and older, conducted July 11-Aug. 10, 2017 and a Pew Research Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. The survey, conducted online in English and in Spanish, included an oversample of employed adults working in science, technology, engineering and math fields. See Methodology for details.

Most women in STEM jobs who work in majority-male workplaces, in computer jobs or who have a postgraduate degree have experienced gender discrimination at work

On average, women working in STEM jobs are more likely than men to say they have experienced workplace discrimination due to their gender. Half (50%) of women in STEM jobs say they have experienced any of eight forms of discrimination in the workplace because of their gender – more than women in non-STEM jobs (41%) and far more than men in STEM occupations (19%). The most common forms of gender discrimination experienced by women in STEM jobs include earning less than a man doing the same job (29%), having someone treat them as if they were not competent (29%), experiencing repeated, small slights in their workplace (20%) and receiving less support from senior leaders than a man who was doing the same job (18%).

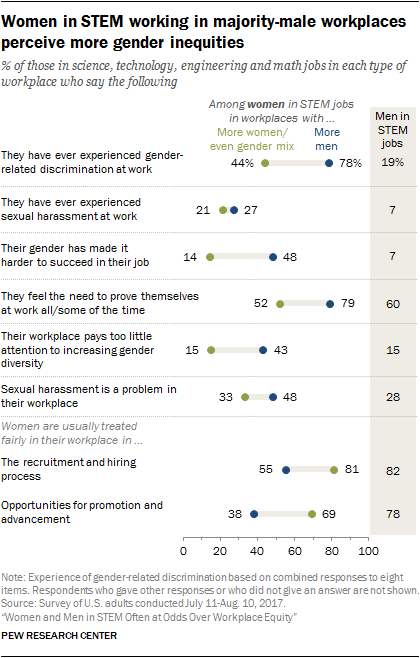

In workplaces where most employees are men, about half of women in STEM say their gender has been an impediment to success on the job

Pioneering work from business school professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter in the late 1970s drew attention to how the structure of organizations – particularly the balance of minority and majority groups – can influence experiences in the workplace.

The majority of women in STEM positions work in majority-female workplaces (55%) or work with an even mix of both genders (25%). But the 19% of women in STEM who work in settings with mostly men stand out from others. Fully 78% of these women say they have experienced gender discrimination in the workplace – compared with 44% of STEM women in other settings.3

About half (48%) of women in STEM jobs who work with mostly men say their gender has made it harder for them to succeed in their job, compared with just 14% of other women in STEM.

One respondent explained it this way:

“People automatically assume I am the secretary, or in a less technical role because I am female. This makes it difficult for me to build a technical network to get my work done. People will call on my male co-workers, but not call on me.” – White woman, technical consultant, 36

Gender balance in the workplace also tends to matter for women in non-STEM positions but those in STEM stand out especially when it comes to experiences with workplace discrimination, the feeling that they need to prove themselves in order to be respected by coworkers, and their belief that, overall, their gender has made it harder for them to succeed at work. By contrast, for male STEM workers, the gender balance in their workplace is largely unrelated to views about gender equity.4

There are similar differences, though less pronounced, among women in STEM jobs by their level of education. Women with a postgraduate degree who work in STEM jobs are more likely than other women in STEM to have experienced gender discrimination at work (62%, compared with 41% of women with some college or less education). Roughly a third (35%) of women in STEM with a postgraduate degree believe their gender has made it harder to succeed on the job, compared with just 10% of women in STEM with some college or less education. And, women in STEM with more education are more skeptical that women where they work are usually treated fairly when it comes to opportunities for promotion (52% of those with a postgraduate degree say women are usually treated fairly vs. 76% of women with some college or less working in a STEM job).

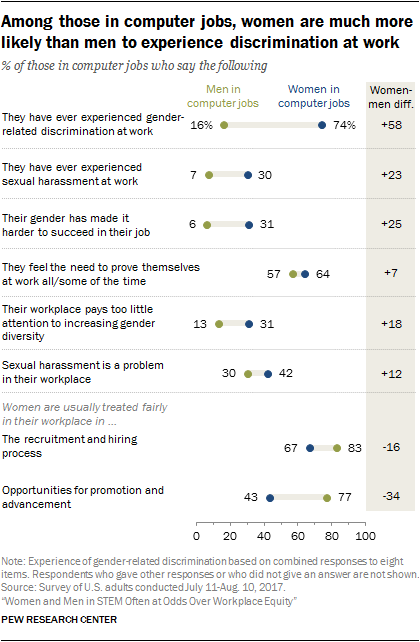

Roughly three-quarters of women in computer jobs say they have experienced gender-related workplace discrimination

Some 74% of women in computer jobs, such as software development or data science, say they have experienced discrimination because of their gender, compared with 16% of men in these jobs.5 (This group includes some who work in the tech industry and some who work in other sectors.)6

Women in computer jobs are less likely than men in such jobs to believe that women are “usually” given a fair shake where they work when it comes to opportunities for promotion and advancement (43% of women in computer jobs say this usually occurs, compared with 77% of men).

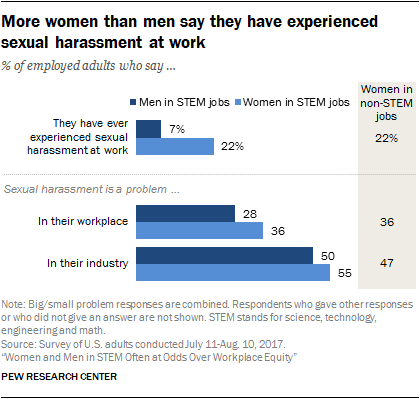

About one-in-five women in STEM and non-STEM jobs say they have experienced sexual harassment at work

In the Pew Research Center survey – conducted before the string of prominent sexual harassment allegations and public discussion of these issues on social media outlets and elsewhere – some 22% of working women in the U.S. say they have experienced sexual harassment at work, compared with 7% of working men. The share of women who say they have experienced sexual harassment at work is the same among those in STEM and non-STEM jobs.7

Women working in STEM are more likely than their male counterparts to regard sexual harassment as at least a small problem in their workplace (36% vs. 28%). As with experience with discrimination, women in STEM jobs who work in majority-male settings and women in computer jobs are particularly likely to say that sexual harassment is at least a small problem where they work. Nearly half (48%) of female STEM workers in majority-male workplaces say that sexual harassment is a problem where they work. About four-in-ten (42%) women in computer jobs consider workplace sexual harassment a problem where they work, compared with three-in-ten (30%) men in computer jobs.

Among those in non-STEM occupations, men and women are equally likely to consider sexual harassment a problem where they work.

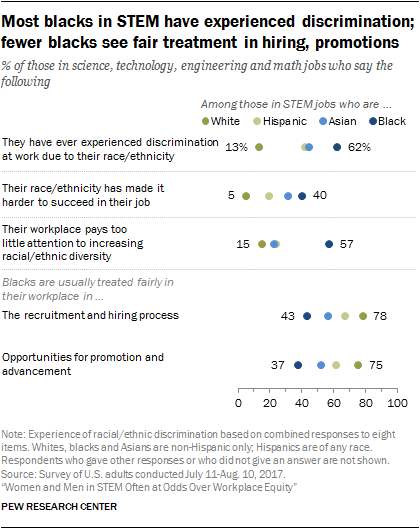

About six-in-ten blacks working in STEM say they have experienced workplace discrimination because of their race

Concerns about the underrepresentation of blacks and other racial minorities – and particularly women of color – in the STEM workforce have been ongoing for at least four decades.8 The Pew Research Center survey finds that, today, black STEM workers are especially likely to say they have experienced discrimination at work because of their race or ethnicity; 62% of blacks in STEM say this, compared with 44% of Asians, 42% of Hispanics and just 13% of whites in STEM jobs.

Blacks in STEM jobs tend to report experiences of workplace discrimination due to race more than blacks in non-STEM jobs (62% vs. 50%).9 Hispanics in STEM and non-STEM jobs are equally likely to say they have experienced workplace discrimination because of their race or ethnicity (42% each).10

And, blacks working in STEM jobs are less convinced than white STEM workers that black employees where they work are treated fairly when it comes to hiring and promotions. In all, 43% of blacks in STEM jobs believe that blacks where they work are usually treated fairly during recruitment; 37% say this is the case during promotion and advancement opportunities. By contrast most white STEM workers believe that blacks are usually treated fairly in these processes where they work (78% say this about hiring, 75% about advancement processes).

Other Pew Research Center analyses found that black Americans with at least some college experience are more likely to say they have experienced discrimination or been treated unfairly across a range of experiences because of their race or ethnicity, compared with those without any college experience. (There are not enough blacks in STEM jobs in this survey for analysis by levels of education.)

While the majority of STEM workers believe their race or ethnicity has made no difference in their ability to succeed in their job, blacks (40%) and Asians (31%) in STEM jobs, followed by Hispanics (19%), are more likely than white STEM workers (5%) to say it has been harder to find success in their job because of their race or ethnicity.

STEM workers who believe their race or ethnicity has made it harder to succeed provide a number of explanations, including concerns about the hiring process, promotions and pay equity, and stereotypical beliefs among their coworkers. Some respondents put it this way:

“People have preconceived ideas of what I am capable of doing.” – Black man, physical scientist, 39

“This ‘other-ness’ exists intentionally or unintentionally between those of a minority and those of a majority from lacking of common cultural background. Relationships at work appear polite on surface but reluctant tendency in willing to share limited opportunities the same way, which I felt in a previous job where whites and males were overwhelmingly a majority.” – Asian woman, engineer, 56

The STEM workforce has grown, especially among computer occupations

Analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey shows that employment in STEM occupations has grown 79% since 1990 (from 9.7 million to 17.3 million) with the largest growth occurring in computer occupations (338% growth since 1990).

The share of women working in such jobs varies widely both within and across job types (or clusters). Women account for a majority of healthcare practitioners and technicians but are underrepresented in other jobs, particularly computer and engineering positions. While there has been significant progress for women in the life and physical sciences since 1990, the share of women has been roughly stable in other STEM occupational clusters and has gone down 7 percentage points in computer occupations.11

What’s a STEM job?

This analysis relies on a broad-based definition of the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) workforce. STEM jobs are defined solely based on occupation and include: life sciences, physical and Earth sciences, engineering and architecture, computer and math occupations as well as health-related occupations including healthcare providers and technicians.

Educators specializing in STEM subjects could not be identified in the analysis of the American Community Survey, though they are included as holding STEM jobs in the analysis of the Pew Research Center survey.

While there is often considerable overlap across definitions, there is no commonly agreed definition of the STEM workforce. Thus, caution is warranted in any direct comparisons with other studies.

Gains in women’s representation in STEM jobs have been concentrated among women holding advanced degrees, although women still tend to be underrepresented among such workers. Women are roughly four-in-ten (41%) of all STEM workers with a professional or doctoral degree such as an M.D., D.D.S., or Ph.D.

Black and Hispanic workers continue to be underrepresented in the STEM workforce. Blacks make up 11% of the U.S. workforce overall but represent 9% of STEM workers, while Hispanics comprise 16% of the U.S. workforce but only 7% of all STEM workers.

Asians are overrepresented in the STEM workforce, relative to their overall share of the workforce, especially among college-educated workers: 17% of college-educated STEM workers are Asian, while 10% of all workers with a college degree are Asian.

The representation of women, blacks and Hispanics in STEM has implications for the average earnings of workers in these groups. STEM workers earn more, on average, than workers in non-STEM jobs, even when controlling for educational attainment.

One potential barrier for those wishing to enter the STEM workforce is the generally higher level of educational attainment required for many such positions. Among college-educated workers, one-in-three (33%) majored in a STEM field. But only about half (52%) of those with college training in a STEM field are currently employed in a STEM job.12 The rest are working in other fields, with many benefiting from the financial bump in earnings that comes with a STEM degree.

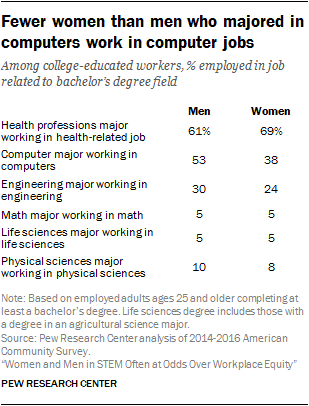

The reasons why half of college-educated workers with STEM-related training turn to jobs elsewhere are likely complicated. Among college-educated workers, those who majored in a health professions field are more likely than those who majored in other STEM fields to be working in a job directly related to their degree. About seven-in-ten (69%) women who majored in a health professions field (such as nursing or pharmacy) are working in a health-related occupation, as are 61% of men who majored in health professions.

But among those who majored in computers or computer science, women are less likely than men to be working in a computer occupation (38% vs 53%). Similarly, women who majored in engineering during their undergraduate studies are less likely than men to be working in engineering jobs (24% vs. 30%). Thus, in two occupational areas with particularly low shares of women, retention of those who meet a key barrier for job entry appears to be lower for women than for men.

Other notable findings include the following:

The public image of STEM jobs includes higher pay and an advantage in attracting young talent compared with other industry sectors

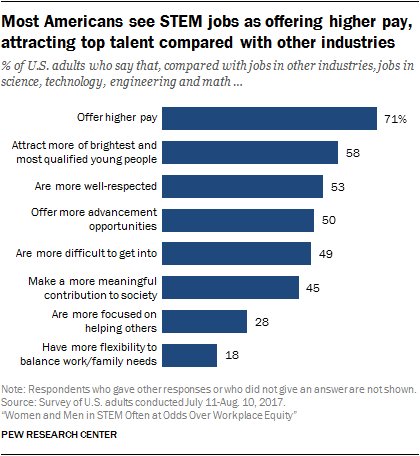

In some ways, the public has a very positive view of STEM jobs, as they compare with jobs in other sectors. About seven-in-ten Americans (71%) see jobs in STEM as offering better compensation than jobs in other industries. And, a majority of Americans (58%) consider STEM jobs to attract more of the brightest, most qualified young people.

The public is closely divided over whether jobs in STEM make a more meaningful contribution to society or do so to about the same extent as other jobs (45% to 48%). But only a minority think of STEM jobs as being more focused on helping others (28%) than jobs in other industries.

About one-in-five Americans (18%) say STEM jobs have more flexibility to balance work and family needs than other jobs in other sectors, while about half (52%) say the flexibility in this regard is about the same as it is in other sectors and 28% say there is less flexibility in STEM jobs than there is elsewhere.

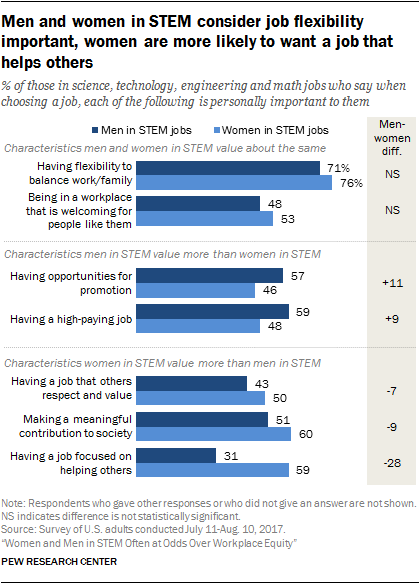

Men and women working in STEM say flexibility to balance work and family needs is important to them

Men and women in STEM jobs – and indeed those in non-STEM jobs as well – say that having the flexibility to balance their work and family obligations is an important factor to them in choosing a job. But men and women in STEM tend to diverge when it comes to other job characteristics. A somewhat higher share of men than women say that having higher pay and opportunities for promotion is important to them in choosing a job. Women in STEM jobs are more inclined to consider a job that focuses on helping others (59%) as important to them compared with men in STEM jobs (31%).13

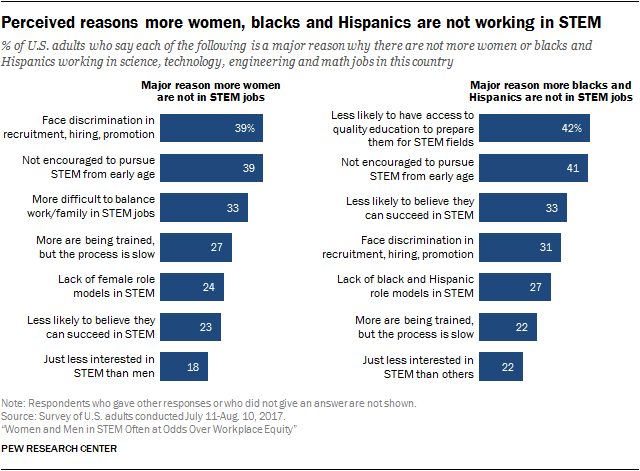

Americans see a range of explanations for the underrepresentation of women, blacks and Hispanics in STEM jobs

Many Americans attribute the limited diversity of the STEM workforce to a lack of encouragement for girls and blacks and Hispanics to pursue STEM from an early age; 39% of Americans consider this a major reason there are not more women in some STEM areas, and 41% say this is a major reason there are not more blacks and Hispanics in the STEM workforce.

In addition, 42% of Americans say limited access to quality education to prepare them for these fields is a major reason blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented in the STEM workforce; this view is held by a majority of those working in STEM who are black (73%) and about half of Hispanics (53%), Asians (52%) and whites (50%) in STEM jobs.

There are wide differences among STEM workers on the role of racial/ethnic discrimination in underrepresentation. Among blacks in STEM jobs, 72% say discrimination in recruitment, hiring and promotions is a major reason behind the underrepresentation of blacks and Hispanics in these jobs. By contrast, 27% of whites and 28% of Asians say this, while 43% of Hispanics think discrimination is a major reason behind the underrepresentation.

Similarly, there are wide differences between men and women working in STEM jobs on the role of gender discrimination. About half of women in STEM jobs (48%) say gender discrimination in recruitment, hiring and promotions is a major reason there are not more women in STEM jobs, compared with 29% of men in STEM jobs.

When women and those in racial and ethnic minority groups working in STEM were asked to say, in their own words, the best ways to attract more people like themselves to STEM, many emphasized the importance of quality schooling and an early start to encouraging people into the field with repeated support over time. A few examples:

“You must introduce those fields early in the elementary school years. Then continue to build on that by establishing STEM clubs and activities. Provide information to parents about local/community STEM events for continued interests. Most of all, make sure that any STEM student has the rigorous preparation that will be needed to get them accepted into college and able to handle the nature of the college level classes.” – Black woman, nurse, 49

“K-8 teaching needs to be designed to make these subjects more interesting and accessible to girls. Teachers need to be explicit about the need for more women in STEM jobs, and help girls feel that they have a reason to pursue these fields in spite of the somewhat intimidating gender breakdown of higher level classes.” – White woman, math teacher, 42

“Providing opportunities such as putting upgraded computers and/or science labs in inner-city schools, libraries and community centers. Black men currently in the STEM industries must be visible to the younger generation in order to show the value of those skills and the career implications.” – Black man, systems engineer, 30

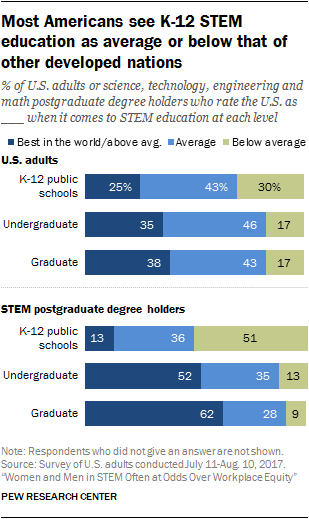

Most Americans rate K-12 STEM education as average or worse compared with other developed nations, so, too, do those with an advanced degree in STEM

Americans are generally critical of the quality of STEM education in the nation’s K-12 schools. A quarter of Americans (25%) consider K-12 STEM education in the U.S. to be at least above average compared with other developed countries, while 30% say the U.S. is below average in this regard, and 43% say it is average. Parents with children in public schools give similar ratings of the nation’s K-12 STEM education.

Americans tend to see higher education in STEM more favorably, by comparison, but there too, fewer than half consider undergraduate education (35%) or graduate education (38%) in STEM as at least above average compared with other nations.

People who, themselves, have a postgraduate degree in a STEM field give positive ratings to the quality of postsecondary education in the U.S., but just 13% of this group considers K-12 STEM education to be at least above average.

Nonetheless, as Americans look back on their own K-12 experiences, three-quarters (75%) report that they generally liked science classes. Science labs and hands-on learning experiences stand out as a key appeal among those who liked science classes. Some 46% of those who disliked science classes in their youth say a reason for their view is that these classes were hard, while another 36% of this group found it hard to see how science classes would be useful to them in the future.

The data in this report come from two sources: 1) a Pew Research Center analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s 1990 and 2000 decennial censuses as well as aggregated 2014-2016 American Community Survey data and 2) a nationally representative survey of 4,914 U.S. adults, ages 18 and older, conducted July 11-Aug. 10, 2017. The survey, which was conducted online in English and Spanish through GfK’s Knowledge Panel, included an oversample of employed adults working in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) jobs.

Analysis of the survey data compares those working in STEM jobs with those in non-STEM jobs based on self-identified occupation. STEM jobs include: computer and mathematical jobs, architecture and engineering, life sciences, physical sciences, healthcare practitioners and technicians, and teachers at the K-12 or postsecondary level with a specialty in teaching science, technology, engineering or math subjects.

A similar definition is used to identify the STEM workforce in the U.S. Census Bureau data based on the 2010 Standard Occupational Classification. However, no educators are included as having STEM jobs in that data because the dataset does not allow identification of educators with a subject matter expertise in STEM subjects.

References to the STEM workforce are based on those employed in a job classified as being in science, technology, engineering or math.

Some analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau data compares those with a college degree who majored in STEM and those who majored in other fields. A STEM major includes the following areas: computers, mathematics and statistics, biological, agricultural and environmental sciences, physical and earth sciences, engineering, architecture, health-related fields, such as nursing, and STEM education, like science or math teacher education. Some analysis of the survey data is based on those with a postgraduate degree in a STEM field, using the same definition as above.

References to whites, blacks and Asians include only those who are non-Hispanic and identify themselves as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

Asians working in STEM jobs are based on those who self-identify as Asian or Asian American and work in occupations classified as STEM. There are too few Asians working in non-STEM jobs in the survey for separate analysis. Note that the survey was conducted in English and Spanish only; thus only Asians proficient in English/Spanish are likely to have completed the survey. For more on the characteristics of the Asian population in the U.S. see the Center’s fact sheets on Asian Americans.

References to college graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a bachelor’s degree or more, unless otherwise noted. “Some college” includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a degree. “High school or less” refers to those who have a high school diploma or its equivalent, such as a General Education Development (GED) certificate, or less education. References to those with advanced degrees and postgraduate degrees are used interchangeably; these terms refer to people who have a master’s degree or higher.